Now for the science behind movement.

Take more notes. This will be very useful.

-

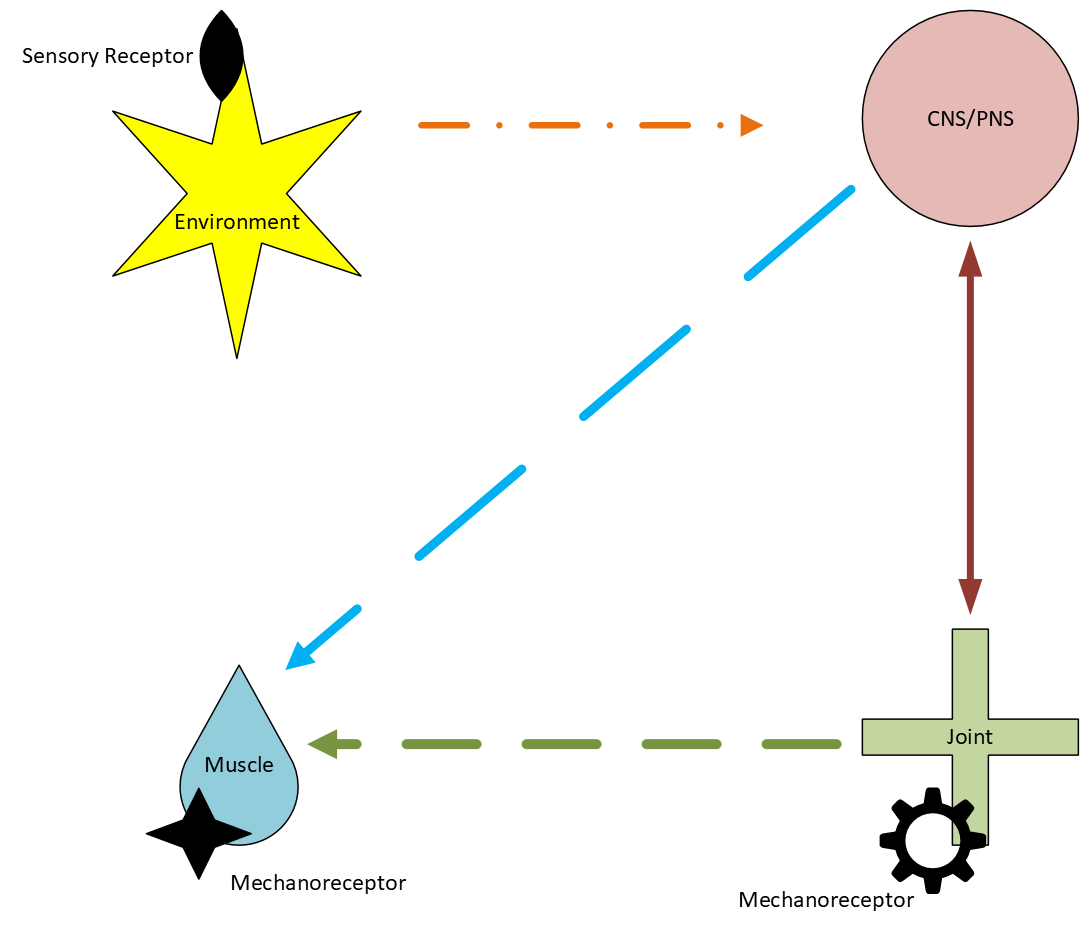

Neural control of movement (Neuromechanics) is the interplay between neural circuits and biomechanics that gives function to anatomical structures, allowing an individual to interact with their environment. The biomechanical properties of the musculoskeletal system and its interaction with the central and peripheral nervous system to create movement, make these systems difficult to separate. The ability to move through an environment includes the interplay of joints, muscles, the peripheral nervous system, the central nervous system, sensory receptors and mechanoreceptors. Neuromechanics provides a mechanism to translate gross motor functions into detailed muscle activation patterns.

Neuromechanics is the study of how muscles, sense organs, motor pattern generator and the brain interact to create coordinated movement. Neural control of movement gives rise to an individual’s ability to synthesize information correctly from the environment to the brain and spinal cord, traveling to the muscles and back to the brain. Coordinated movement is formed among the interaction between descending output messages from the central nervous system and sensory input messages from the body and environment. Information from sensory receptors found in the joints and skin interact with the environment and surrounding objects exchanging energy and momentum. The gathered information is then transferred to the central nervous system. This creates a sequence of activated muscle synergies that allow a specific, functional movement pattern and adequate posture. The central nervous system uses many different combinations of just a few muscle synergies to produce a wide range of motor behaviors.

The motor commands from the central nervous system trigger force development in muscles, which drive movement and control the mechanics of the body. The nervous system and the muscles interact at the joint level. Muscles drive the body's motion via information and torque from the joint it is overlapping. The ability for a joint to maintain its preferred movement path, where a joint moves pain-free with least resistance, allows for optimal muscle activity. The inertia and shape of the muscle determines the trajectory of the motion.

An individual has a limited set of existing muscle synergies to use for a certain task. Because motor patterns are constrained by the availability of muscle synergies, motor performance for an individual does have its limits. The control of a motor task, with an obvious range in performance, descends from the brain to lower level muscle synergies and is subject to proprioceptive (joint) and environmental feedback. Slow to fast running, small to large jump distance or quiet to loud speaking are all determined through this network that transforms the simple command into coordinated muscle-tendon actions distributed over different limbs and joints. The interaction between the anatomical structure, the neuromechanics and the biomechanical system with the environment ultimately determines the appearance of the performed action.

-

The mechanical locking mechanisms are associated with the arthrokinetic reflex that alters the surrounding muscle tone to improve joint stability and protect the joint from excessive movements. The nervous system alters muscle activity in response to joint movement and position at the level of the articular receptor. Mechanical joint dysfunction causes irritation at the joint level, which causes a protective, secondary spasm and inhibition of muscle activity.

The primary function of the sensory nerve to a joint is to detect and transmit mechanical information from the joint to the central nervous system. All synovial joints are innervated by sensory nerves from more than one spinal segment. Therefore, complete obstruction to a nerve’s conduction can never abolish all innervations to a joint. Joints are supplied by two different types of nerves: the primary and the accessory articular nerves. The primary articular nerves are the branches that originate directly from a main nerve trunk. The accessory articular nerves are branches of nerves that innervate nearby muscles, skin and periosteum.

Ligaments and joint capsules function not only as support structures, but also as a source of afferent input from a variety of sensory receptors to the central nervous system regarding muscle tone. Slow adapting type I receptors in the same stretched area of the joint capsule maintains the arthrokinetic reflex to the adjacent muscles as long as the capsule is on stretch. The stretch can occur with movement or swelling. Effusion changes the response of the articular receptors and will increase the discharge rate of the receptors.

In the joint capsule, the greatest number of receptors is found in those parts of the joint most subject to variation in tension during movement. In the knee and the elbow the greatest number of receptors is found anteriorly and posteriorly where the movement is the greatest and therefore requires the most control of muscle tone. When the joint is about to leave its normal range of movement, type II receptors fire to elicit increased muscle tone and protection. These warning signals increase in urgency with greater stretch as the higher thresholds type III receptors join the signaling for increased muscle tone.

The arthrokinetic reflex is not only active when the joint exceeds its normal working range, but at all intermediate angles as well. The modulation of muscle tone is accomplished over the entire range of joint movement. As an example, the arthrokinetic reflex working on the gastrocnemius and tibialis anterior muscles controls movement of the ankle joint. Passive ankle dorsiflexion produces increased activity of the gastrocnemius muscle with simultaneous reduction of tibialis anterior activity due to the stretch on the posterior capsule.

-

Irritation is an unpleasant and emotional experience. It functions to protect the body from imminent threat or injury. Pain alerts the brain to danger before the body is injured badly. If there are problems that exist in the joints or immune system, it will hurt if the brain thinks the body is in danger. However, if the brain does not think the body is in danger there may still be problems at the joints, muscles, ligaments, nerves or immune system but it will not hurt.

Pain is not definitive; it just says something is wrong. It does not tell us where or how much. Pain is not necessarily a bad thing, rather helpful at times. Pain makes us move, think and behave differently, which makes it vital for healing. At any one time, around twenty percent of people have pain that has persisted for more than three months. Chronic pain lacks the acute warning function and continues well beyond normal healing time. The pain mechanism that usually defines chronic pain is the altered central pain modulation and accounts for a significant number of musculoskeletal pain cases without a defined etiology. The altered central pain modulation is defined as a dysregulation of the nervous system causing hypersensitivity to not only noxious stimuli but also normal stimuli. There is an increase in excitation and a decrease in inhibition by the central nervous system to the information gathered from pain receptors. As central sensitization persists, activity limits decrease. Understanding pain’s physiology changes the way people think about pain, minimizes the threat, and improves the management of it.

Pain originating on one side of the body will be felt on the same side. All cervicothoracic and lumbosacral tissues are able to cause localized back pain or pain down the upper or lower extremity respectfully, which is called somatic referred pain. It is the central rather than the peripheral nervous system that is responsible for somatic referred pain. The subjective experience of pain is the result of processing the afferent impulse at the spinal cord, brain stem, and the cerebral cortex levels. Referred pain tends to be felt distal to its origin, and the stronger the stimulus, the larger the area of the pain reference. Pain felt in a certain dermatome must arise from a structure with the same segmental innervations. Irritation of structures located deep in the body refers pain to a larger area than superficial irritation.

Pain from a joint depends on type IV afferent receptors. These nociceptors, or pain receptors, are located throughout the joint, having been identified in the capsule, ligaments, menisci, periosteum and subchondral bone. Nerve endings are found in the fibrous capsule, including the capsular ligaments, in the intracapsular and extracapsular ligaments and in the subintima including the adipose tissue.

Lumbar facet joint capsules are richly supplied with encapsulated corpuscular endings identified as ruffini-type endings. These receptors help to ensure postural stability. It is within these bead-like structures that joint pain originates. The afferent information from Type IV articular receptors projects to the spinal cord and synapses with the neurons in the gray matter that ascends to the brain. On reaching the cortex of the brain, the nociception produces the experience of pain.

The amount of joint pain experience depends on the amount of chemical or mechanical irritation of a joint and the amount of afferent activity from articular and other related mechanoreceptors. When a noxious movement is applied to a joint the firing rate of the afferent nerve significantly increases. However, activity of the mechanoreceptor afferents from the same or related tissues inhibits nociception at those tissues. Movements, active or passive, stimulate articular mechanoreceptors and results in the inhibition of pain. Active or passive movements to a joint are possibly more effective in relieving joint pain because it derives from the same tissue as the nociception from that joint. When therapy has the option of addressing a number of tissues, skin, muscle and joint, to decrease pain, working at the level of the joint may be most effective.

-

A spasm is a prolonged continuous contraction of a muscle. Stitch, cramp, charley horse are all loosely used to describe a spasm. A muscle spasm can occur in any muscle and is rarely a primary phenomenon. Muscle spasms are an involuntary guarding as an expression of the arthorkinetic reflex to protect a painful body part. A muscle spasm is the most common manifestation of musculoskeletal pathology.

Hilton’s Law states that an overlying muscle is innervated by the same nerve trunk as that of the adjacent joint.

The articular mechanoreceptors provide continuous information to the gamma motor neuron throughout the range of the joint. Activation of the mechanoreceptors contribute to the continuous modulation of muscle tone and increases the joint’s functional stability.

Researchers found an almost linear relationship between the pressure inside a joint and the discharge rate of the articular mechanoreceptors. A spasm occurs as a guarding or splinting to prevent painful movement. A muscle spasm is universally acknowledged as a protective phenomenon when it is associated with, for example, an acute abdominal pathology, an untreated fracture, or an unreduced dislocation. Somewhat less painful conditions are also associated with muscle spasm, such as spasm occurring secondary to a virus, a cold, a contusion or a muscle tear.

With joint pathology, a spasm also occurs. Muscle spasm does not differentiate between smooth muscle and skeletal muscle. Skeletal muscle encompasses the group of muscles that move joints. Smooth muscle makes up the internal organs. Pain will cause tightening of both muscle types, from intestines to the gastronemius muscle. The muscle tone changes can be expected on the same side of the body as the irritation. The stronger the stimulus, the more pronounced the spasm and the greater the function loss. Deeper lesions express themselves more prominently in muscular reactions than superficial issues.

-

Inhibition is the activation of pain receptors initiating nociceptive activity at the spinal cord which alters efferent motor activity and therefore the timing and degree of muscle activation. Reflex inhibition of a muscle will present as weakness. Inhibited muscles display decreased activity in general. In extreme cases the muscle may remain nearly silent on EMG. Inhibition can occur independent of pain. Reflex inhibition can be observed with capsular compression, ligament stretch, joint movement, joint injury and operative trauma. The potential causes of inhibition may include inactivity or immobilization of muscles, circulatory disorders, aging, myopathy, nociception, and disorders of nerve conduction.

After dislocation of the elbow, the biceps muscle is incapable of contracting when a certain range of joint movement has been exceeded. A study demonstrated an increase in activity of Type I and II articular receptors at the knee joint after it was injected with distending fluid. Researchers observed a weakness of the quadriceps muscle in the presence of knee joint effusion. The amount of quadriceps inhibition was strongly related to the amount of pressure inside the joint. Anesthetic injections abolished the inhibition suggesting that the receptors are located intra-capsular.

Two reflex mechanisms seem to inhibit quadriceps strength in the presence of a persistent knee effusion, one mediated by pressure sensitive receptors, the other still unknown. It has been shown in experimental and postoperative effusions that the removal of fluid is followed by a fall in intra-articular pressure and a rise in the strength of a quadriceps muscle contraction. One study found that maximal quadriceps strength without removing the fluid from the knee was significantly lower and the effects of quadriceps exercise was significantly decreased.

The most common treatment for muscle weakness is strengthening exercise. This is only helpful when the muscle weakness is due to a de-conditioned state rather than reflex inhibition. Performing quadriceps exercises, such as quad sets, is considered an ineffective way to strengthen the muscles if an effusion is present. The cause of inhibition needs to be addressed first, or the inhibited muscle will only be able to contract sub maximally. If a joint with a restricted movement is mobilized to normal range of motion, then a previously inhibited muscle will test stronger immediately after the mobilization.