The human body consists of 150 joints that cannot be dissociated from one another regarding overall movement. Movement of one joint will affect several nearby joints. During examination, asymmetry of posture and restriction of active and passive range of motions will be noted. Abnormal movement patterns can also be apparent.

When making judgments about the quality of a patient’s motion remember that there is the possibility of inter-subject differences. The difference between an individual’s right and left sides is more important to your evaluation than the difference between an individual’s range of motion and the “normal” value found in the literature. The clinician must evaluate the uninvolved side to help establish the patient’s “normal” range of movement. There is no way of telling what a patient’s normal range of motion is the first time they are evaluated. It may be far removed from one’s idea of what normal should be and may not be discovered until treatment is complete. The goal of the examination is to compare the targeted joint on both sides of the body and use symmetry of tissue pliability to indicate the resolution of mechanical joint dysfunction following treatment.

-

Palpation is important. Cervicothoracic mechanical dysfunction will be accompanied by a muscle spasm, most likely found in the rhomboids, the infraspinatus and the levator muscles. However, all muscles around the dysfunction will tighten, so palpating the smaller muscle groups will also give you information.

Next, compare right and left passive cervicothoracic side bend and rotation with the patient in supine. Travel to the end ranges of the movement with the patient in a passive, relaxed position and move slowly and gently. Recognize the right and left end feels and compare side to side. Is it soft, or firm, painless or painful? This will determine if there is a difference right to left. Compare the strength of right cervicothoracic rotation to the left. Is one side stronger than the other? Is motion to one side painful or hesitant?

-

TMJ dysfunction will be accompanied by a secondary spasm of the levator and the masseter muscles. While palpating, compare opening and closing of the jaw at the TMJ joint. Is one side translating more than the other, or not at all? Is the joint rolling and then translating, or is it just translating?

The TMJ evaluation must also include a cervicothoracic evaluation as full TMJ movement can only be achieved with full neck and thoracic movement.

-

Shoulder movement does not stop at the shoulder. It involves the thoracic spine, and the elbow as well. The shoulder is only a small part of the entire kinetic chain, but often feels the brunt of mechanical joint dysfunction because it demands such joint interplay to allow full movement.

Palpation of the muscle groups is always a good place to start for an examination. Palpate and compare the right and left levator, infraspinatus, rhomboids and scalene muscles to begin. The narrow triangular opening formed between the anterior scalene, the middle scalene, and the attachments on the first rib, allows passage of the subclavian artery and the brachial plexus. Compression of these structures caused by secondary muscle spasm can lead to symptoms such as diminished sensation, weakness, the sensation of pins and needles, and pain radiating down the arm. A stretch of the pectoralis minor muscle in spasm can also compress these sensitive structures and cause symptoms as the nerves and vessels pass through this muscle.27

After palpating for muscle spasm, assess shoulder strength in a seated position. Check abduction, adduction, internal and external rotation, and flexion and extension in the neutral position. Judge if the movement is strong or weak, painless or painful and if the contraction is consistent or not. Remember that strength can be an inhibition as a well as a true soft tissue change. If movement is strong and painless, the soft tissue is intact. If it is strong and painful or even weak and painful, the soft tissue is still intact. This strength discrepancy is then most likely due to a reflex inhibition and should be re-assessed after the mechanical joint dysfunction has been resolved to see if strength has increased or not. If the tissue is not intact, even when the mechanical joint dysfunction is resolved, the muscle will continue to be weak and painless.

Next, with the patient supine, assess the movement quality and end feel of right and left passive cervicothoracic side bend and rotation. Is it firm or soft? Is it painless or painful? Does the patient’s facial expression change? Compare right and left shoulder flexion in neutral, bringing the shoulder to the full, end range movement and comparing the end feel. You can also look at internal and external rotation, comparing the end ranges for pain, mobility and end feel.

-

The elbow evaluation also includes the cervicothoracic, the shoulder and the wrist. To assure a full evaluation of mechanical movement, begin with the cervicothoracic and shoulder mechanical evaluation and then continue to the elbow.

Begin with palpation. The pronator teres and the biceps brachii muscles are easy muscles to palpate for spasm and to compare right to left. Mechanical joint dysfunction at the humeral-ulna joint will lead to secondary irritation and muscle spasm above and below the joint, just as it will at any joint.

With tightness of the biceps brachii muscle comes reduction in elbow extension and pronation/supination range of motion.27 Assess the end feel of elbow extension. Is it painful or painless? Is it firm or soft? How does it compare to the other side? Also look at forearm supination at 90 degrees of elbow flexion with the patient seated. Again, how is the end feel? Soft? Tight? Firm? Painful or Painless? It is often helpful to assess supination and pronation for side to side comparison at the same time with the patient sitting in front of you, arms relaxed at 90 degrees.

Then assess grip strength and wrist movement. Grip strength will decrease with mechanical joint dysfunction and related muscle spasm due to secondary inhibition. Assess range of motion and the end feel of wrist flexion, extension, varus and valgus, and compare to the other side.

-

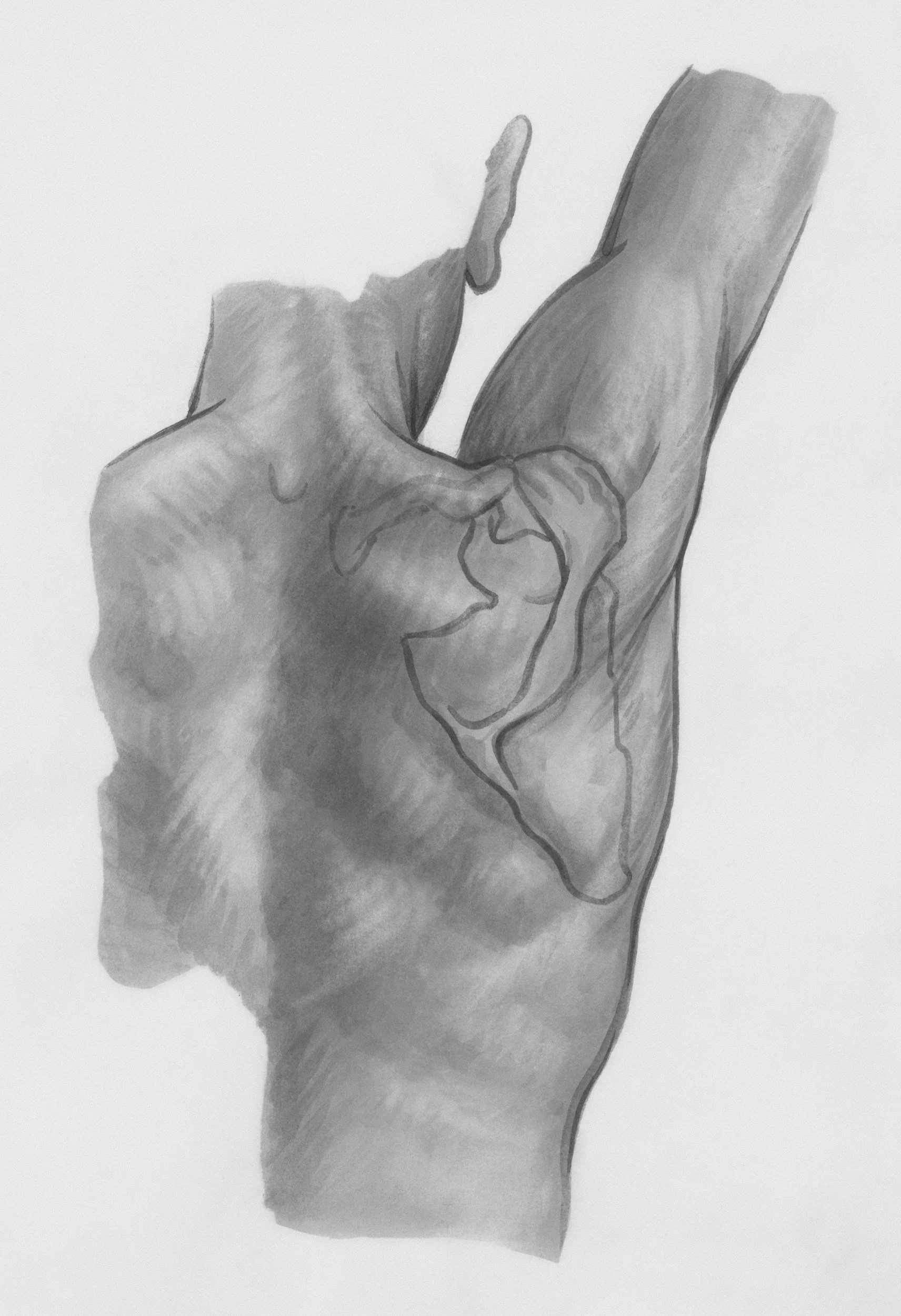

Wrist and hand movement also includes the elbow. Begin with the elbow mechanical evaluation and then continue with the wrist. Palpation should include the biceps brachii muscle and the pronators and supinators as all of these will tighten up with a wrist and elbow mechanical dysfunction. Assess elbow end range extension, forearm supination and pronation, wrist flexion and extension, and wrist varus and valgus, and determine the difference between the end feels right and left. Is the end feel firm or soft, painless or painful? Grip strength of both sides should also be assessed as it will decrease due to the secondary inhibition if mechanical joint dysfunction is present.

-

To examine the lumbosacral area, an easy place to begin is with palpation of the PSIS level right and left in a seated position. As the level is being assessed, focus on the tissue pliability as well as a side to side comparison. Is one side tighter than the other? Is one side tenderer than the other? Assessing tissue pliability with palpation at the right and left Baer’s point, just above the iliac crest, will also add helpful information.

In addition, strength testing is important. Test isometric hip adduction and abduction strength in supine with knees bent. It is the easiest to have the client squeeze their knees together against the length of your forearm. A passive right and left straight leg raise in supine is also an effective way to compare movement and tissue pliability between sides.

-

The hip evaluation always begins with the lumbosacral mechanical evaluation, because the hip cannot move independent of the lumbar spine and pelvis. Internal and external rotation of the right and left hip should then be compared. Compare the end feel. Is it bony or soft, stiff or springy? Is it painful or painless? Strength of internal and external rotation of the hips can also be compared. You can isolate the hip joint by bringing the knee and hip to 90 degrees and then rotating both ways to test the end feel and compare passive movement at the joint. This will give you an indication of whether the pain is truly from the hip joint or actually referred from the lumbar-pelvis region.

-

Just like the hip, the knee evaluation should begin with the lumbosacral mechanical evaluation. The knee, hip, pelvis and lumbar regions all work together to create full, functional movement. If one component is dysfunctional it is very likely that another is as well.

Begin with palpation. The quadriceps and hip adductor muscles are large muscle groups that are easy to palpate for spasm. Then palpate the ligaments. When palpating the ligaments remember that a ligament is never tender on palpation unless the ligament itself is injured, or there is something wrong with the joint that the tender ligament supports. The medial collateral ligament (MCL) is connected the medial meniscus, so an MCL that is intact and tender will most likely indicate a meniscal restriction. The meniscus can lock the joint mechanically causing joint dysfunction and pain.39 Rarely does a torn meniscus cause pain, unless it has flipped on itself or is impeding joint movement.

The mechanical evaluation will then continue with passive range of motion. Compare the passive end range knee flexion, extension, recurvatum and medial and lateral tibial rotations. How does the end feel present? Is it soft or firm? Is it a bony end feel? Is it painful or painless? How does it feel compared to the opposite side? The tibial rotation is easily assessed in supine with the knee bent and the ankle locked into DF. It is also helpful to compare the strength of the medial and lateral tibial rotation. Is it hesitant or strong? Is it painful or painless?

-

Begin with palpation of the right and left calf muscles and the Achilles tendon. This is a large muscle group and a large tendon, making it easy to compare sides for muscle spasm.

With the patient seated, knees extended, and the ankles supported on the treatment table, compare right and left calcaneal and forefoot varus and valgus. Is the end feel soft or firm? Is it painful or painless? Does one foot have more range than the other? Then compare the strength of the right and left forefoot moving into eversion and inversion. Is it hesitant or strong? Is it painful or painless? Compare the degrees of dorsiflexion and the end feel. Also compare where the stretch is felt by the patient side to side. With full ankle mechanical movement, the dorsiflexion stretch should be felt high in the calf. If it is not, it is a good indication that mechanical joint dysfunction is present.