Now that you know the 5 different movement dysfunctions, you can differentiate them by using a systematic approach that links the client's subjective complaints and your objective findings to the specific movement dysfunction.

SUBJECTIVE

The subjective is the information the patient provides about their condition, symptoms, and medical history. This is the patient's narrative, which is crucial for forming a hypothesis and guiding the rest of the evaluation.

-

When gathering subjective information, we ask a series of open-ended questions to encourage the patient to provide a detailed narrative of their condition. These questions are designed to cover all aspects of the patient's experience, from the onset of the problem to their goals for recovery.

-

Where does it hurt? When did it start? Any numbness or tingling? How is sleep? When does it hurt? How is exercise? How is it in the mornings? Is there swelling? Is there bruising? Is there numbness?

ACTIVE VS PASSIVE ROM

Looking at active range of motion (AROM) and passive range of motion (PROM) is a fundamental technique in physical therapy to help differentiate the cause of a patient's symptoms and guide diagnosis.

-

Active ROM is the amount of joint movement a person can achieve on their own, using their own muscles. It's a measure of their muscle strength, motor control, and willingness to move. When a therapist asks you to lift your arm overhead as far as you can, they are assessing your AROM.

-

Passive ROM is the amount of joint movement a therapist (or an external force like a machine) can achieve while the patient's muscles are completely relaxed. It measures the joint's structural integrity, the flexibility of the surrounding ligaments and tendons, and the absence of any physical blockages.

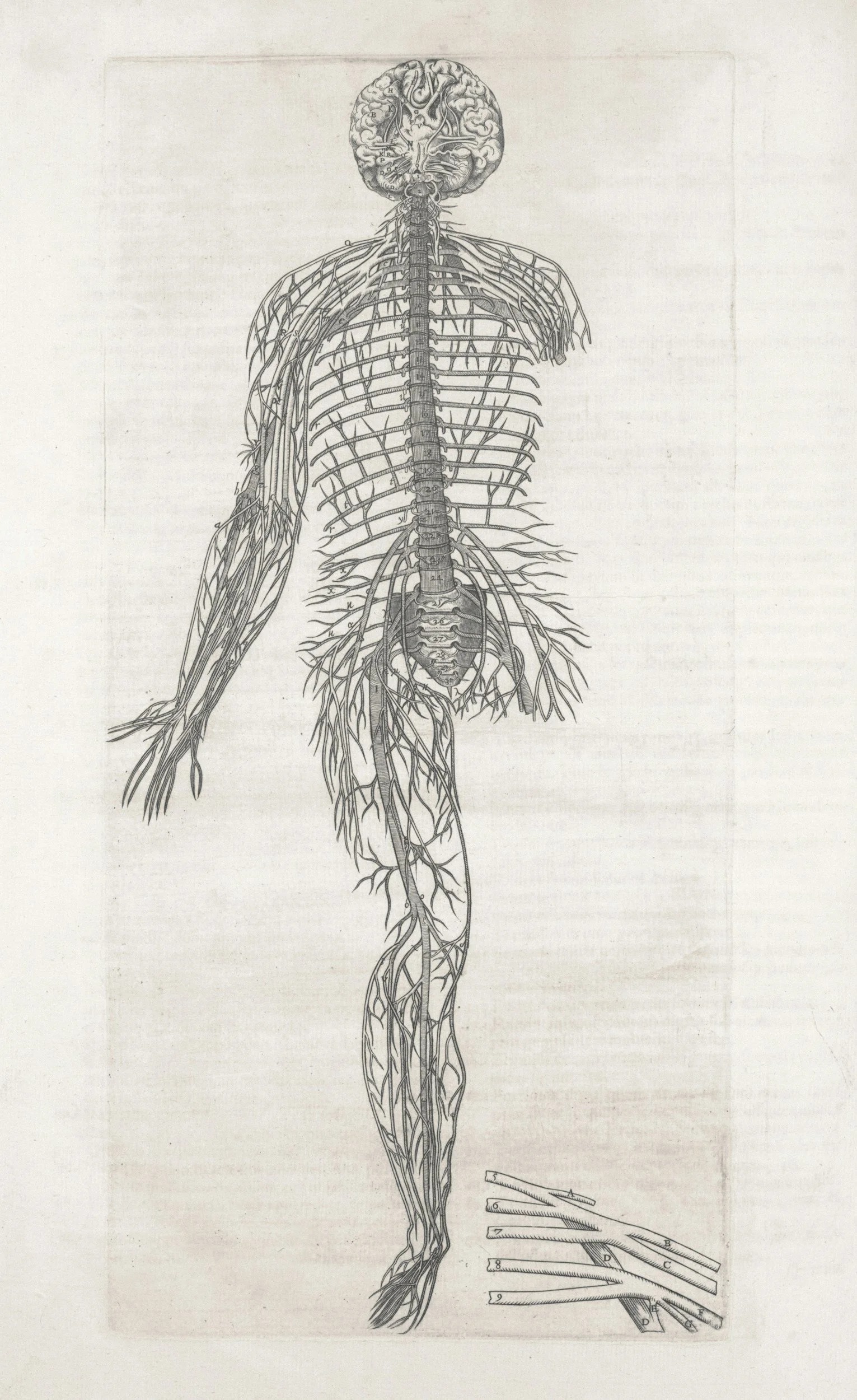

NEURAL SIGNS

Decreased reflex, decreased strength in a myotomal pattern, and numbness in a dermatomal pattern—are classic indicators of peripheral nerve dysfunction. They demonstrate how damage to a peripheral nerve, which is a nerve outside of the brain and spinal cord, disrupts the specific signals it carries.

-

When a peripheral nerve is damaged, this entire communication pathway is compromised. The sensory signal can't get to the spinal cord correctly, or the motor signal can't get to the muscle, or both.

-

A reflex is an involuntary, rapid response to a stimulus. It relies on a "reflex arc," which is a simple circuit involving a sensory neuron, the spinal cord, and a motor neuron. For example, the knee-jerk reflex involves a sensory nerve that detects a stretch in the patellar tendon, which then sends a signal to the spinal cord. A motor nerve then immediately sends a signal back to the quadriceps muscle, causing it to contract.

-

A myotome is a group of muscles innervated by a single spinal nerve root. Unlike a peripheral nerve that might supply multiple muscles, a spinal nerve root supplies a specific group of muscles that work together to perform a certain movement. For example, the C5 nerve root primarily controls shoulder abduction (lifting your arm away from your body).

-

dermatome is a specific area of skin that is supplied with sensation by a single spinal nerve root. Think of it as a map of the skin, with each spinal nerve responsible for a distinct zone. For example, the L4 dermatome covers the knee and the inner part of the lower leg.

END FEEL

End feel is the unique sensation that a clinician feels in their hands when they move a joint to its absolute end range of motion. By assessing this resistance, we can determine if the limitation is due to a normal anatomical structure or a pathological issue.

-

a hard, abrupt, and unyielding sensation felt when a joint's passive range of motion is limited by two bones making contact.

-

It is not a distinct type of end feel but rather a description of a painful response that the patient exhibits at the end of the passive range of motion.

-

A firm, springy resistance from muscle tension. It feels like stretching a thick rubber band.

-

A tight end feel is a type of abnormal firm end feel. It's characterized by a firm, unyielding resistance that is felt before the normal anatomical range of motion is achieved. Unlike a normal firm end feel, which has a slight give (like stretching a piece of leather), a tight end feel offers very little to no give and is often painful.

-

no mechanical resistance, as the patient stops the movement due to severe pain before the joint's true anatomical limit is reached, or there is no longer a ligament/muscle to resist the end range.

PALPATION

We palpate during an evaluation to gather information through touch. Palpation is a diagnostic technique where a clinician uses their fingertips to feel the tissue for spasm, temperature, atrophy, stability or laxity. This provides crucial information that may not be apparent through visual inspection alone.

-

A muscle spasm is one of the most useful diagnostic signs that something is wrong in an underlying structure. No one can fake a muscle spasm. Palpation is the method used to diagnose a muscle spasm. The patient must be relaxed and each aspect of the joint being examined must be supported and protected from unguarded, painful movement that could confuse the examination. The examiner must be relaxed and the grasp must be firm and protective, but not restrictive. The clinician must keep in mind that a muscle spasm is only a sign of pathology. The first step to evaluation and treatment is to successfully determine what structures are causing the muscle spasm. These structures are then targeted for treatment and the clinician, and often the patient, will be able to immediately recognize a decrease in the muscle spasm.

A spasm is a prolonged continuous contraction of a muscle. Stitch, cramp, charley horse are all loosely used to describe a spasm. A muscle spasm can occur in any muscle and is rarely a primary phenomenon. Muscle spasms are an involuntary guarding as an expression of the arthorkinetic reflex to protect a painful body part. A muscle spasm is the most common manifestation of musculoskeletal pathology.

Hilton’s Law states that an overlying muscle is innervated by the same nerve trunk as that of the adjacent joint. The articular mechanoreceptors provide continuous information to the gamma motor neuron throughout the range of the joint. Activation of the mechanoreceptors contribute to the continuous modulation of muscle tone and increases the joint’s functional stability.

Researchers found an almost linear relationship between the pressure inside a joint and the discharge rate of the articular mechanoreceptors. A spasm occurs as a guarding or splinting to prevent painful movement. A muscle spasm is universally acknowledged as a protective phenomenon when it is associated with, for example, an acute abdominal pathology, an untreated fracture, or an unreduced dislocation. Somewhat less painful conditions are also associated with muscle spasm, such as spasm occurring secondary to a virus, a cold, a contusion or a muscle tear.

With joint pathology, a spasm also occurs. A muscle spasm does not differentiate between smooth muscle and skeletal muscle. Skeletal muscle encompasses the group of muscles that move joints. Smooth muscle makes up the internal organs. Pain will cause tightening of both muscle types, from intestines to the gastronemius muscle. The muscle tone changes can be expected on the same side of the body as the irritation. The stronger the stimulus, the more pronounced the spasm and the greater the function loss. Deeper lesions express themselves more prominently in muscular reactions than superficial issues.

-

Feel for variations in temperature, such as areas that are excessively warm, which may indicate inflammation or infection, or areas that are unusually cool, which could suggest poor circulation.

-

The most significant sign of a tear is localized tenderness, or sharp pain in a specific spot. This tenderness will feel disproportionate to the amount of pressure you apply.

Gap or Indentation: In a severe, Grade III tear, you may be able to feel a palpable defect or gap in the muscle belly, where the muscle fibers have completely separated. The surrounding area may feel swollen or boggy.

-

Palpating for swelling, or edema, is a key part of a physical assessment. The technique helps you determine not only if swelling is present, but also its characteristics, which can provide clues about the underlying cause. Where is the swelling - muscle, tendon, joint capsule, will also give you valuable information.

-

Bruising can be a key indicator of the nature and severity of an injury.

MUSCLE RESISTANCE

We test muscle resistance during a movement evaluation to assess a muscle's strength and neurological function. This process, often called manual muscle testing (MMT), helps a clinician determine if a muscle is truly weak, inhibited, or functioning as expected. It's a foundational part of a neurological and orthopedic exam because it provides critical information for diagnosis and treatment planning.

-

Muscle resistance is the external force applied by a physical therapist to a patient's limb or body part to assess the strength of a specific muscle or muscle group. This is a key part of manual muscle testing (MMT), a fundamental procedure used to objectively measure a muscle's ability to contract and generate force.

-

In physical therapy, true weakness refers to a reduction in muscle strength that is caused by a problem with the neuromuscular system itself—the brain, spinal cord, peripheral nerves, or the muscle tissue. This is different from weakness that's a result of other factors, like pain.

-

Muscle inhibition is the neurological process of a muscle's ability to contract being "turned down" or "shut off" by the nervous system. It's an internal, involuntary process often triggered by an injury, pain, or inflammation. Unlike true muscle weakness, which is a deficit in the muscle itself or its nerve supply, inhibition is a protective mechanism that reduces muscle activation to prevent further damage.